By Stephen Antonson, with Kathleen Hackett

A few months ago, I found myself standing in the Paris atelier of the sculptor Philippe Anthonioz, who, to my mind, has always represented the living connection to the Giacometti brothers Diego and Alberto, whose names are synonymous with plaster and bronze furnishings, objets d’art and lighting. I had just spent several hours in the Picasso Museum, housed in one of the hotel particuliers in the Marais, strolling rooms filled with its namesake’s work paired with that other giant of modern art, Diego Giacometti….

Despite the fascinating dialog between the pieces on the walls and plinths, my eyes were drawn up to the ceiling, to the iconic chandeliers that hang in every room. I noticed that the grandest lantern that had once hung over the grand staircase had been moved to the foyer on the second floor after the museum’s recent renovation. Many of them threw cold blue light, another change. When I mentioned this to Anthonioz, he nodded his head, as if to share my dismay. Then he casually said, “Yes, I worked on those chandeliers.”

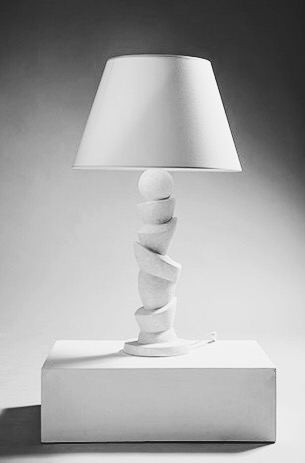

My fascination with plaster of Paris ostensibly began in 1999 with a chance visit to the Union Square studio of Tom Donahue, then the reigning plaster expert in New York. His work ranged from repairing the Statue of Liberty’s broken ear to creating quatrefoil ceilings and outdoor fountains for private clients. Tom has since moved to Garrison, New York, and I often wonder if the Giacometti table lamp he pulled down from a high shelf that day inspired the move. “This is my retirement,” he laughed as he handed me the Lampe de Tête. At the time, my studio practice revolved around graphite drawings of repetitive motifs, many of them faintly rendered urban landscapes “shaped” by removing some of the markings with an eraser. On visiting Tom, I immediately sensed a connection between these barely-there markings and the shadow play of light on plaster. I also loved the baking analogy he used to describe his methodology. Flour and water, depending on how it is treated, yields infinite possibilities. It is the same with gypsum and water.

The truth is that sculpture has interested me since high school and thereafter as a sculpture and painting student at Carnegie Mellon University. But it wasn’t until I spent a semester at the Lacoste School for the Arts in the south of France that I experienced how the human hand can so profoundly make its way into the environment. The school’s founder, Bernard Pfriem, insisted that we get out of the studio and immerse ourselves in our surroundings, where every signpost, stone house, castle, fountain, curb and wall are built by hand. I carved stone for the first time there and fell in love with how tools behave depending on their holder.

The sensibilities that I was awakened to in the South of France were refined on the repeated trips to Paris that followed; little did I know then that this city would be the source of the raw material that has sustained me for the last two decades.

Named for the huge gypsum deposits of Montmartre, plaster of Paris’ appearance as a sculptural medium dates to Mesopotamia, when classical statues were draped in fringed gypsum skirts and dresses. From the Tigris and Euphrates the material made its way into Western European history through architectural details, columns, pilasters, and mouldings.

And torchieres recalling palm trees. But that wasn’t until the 1930s, when Parisian Serge Roche, the son of a well-connected painter and art dealer (Picasso, Renoir, and Pissarro paid regular visits to his Montmartre studio), shaped plaster in what came to be known as ‘Panache’ style, a glorious mix of baroque extravagance and rough naiveté. His plaster lion-footed stools in wood and mirror were a favorite of Elsie de Wolfe, and when Syrie Maugham settled in the Pavilion she rented from the Rothschild’s at Eythrope in Buckinghamshire, she ordered her fireplaces, consoles and palm-shaped capitals from Roche.

Dolphin, shell and palm frond-shaped console bases animated the all-white interiors that came to define her as the most celebrated interior designer of her time.

Across the Atlantic, Frances Elkins, newly divorced, began decorating the homes of her Pebble Beach friends to support herself and her children. Having spent time in Paris while her brother, the architect David Adler, who studied at the Ecole des Beaux Arts, Elkins was drawn to Giacometti’s hand-crafted plaster lamps and Roche’s exuberant pieces. Elkins thrived on eclecticism, and thought nothing of mixing Chippendale, Queen Anne, and Ming pieces with Roche’s fanciful furniture.

At the same time, fellow Parisian Jean Michel Frank, whose taste for ordinary materials and classical lines was turning heads in the city’s Art Deco galleries, was busy espousing his poor luxury aesthetic, tapping his friend Alberto Giacometti to make more than seventy plaster of Paris objets between 1928 and 1939. The horn vases inspired by an oil lamp found in Tutankhamen’s tomb, limpet shell ceiling lights, and lamps adorned with a woman’s bust—Tom Donahue’s Lampe de Tête— are among the most beloved. As Frank’s star shone brighter and brighter, he grew less interested in the materials he used as a young designer—shagreen and parchment— and the chalky white stuff, which was once just filler, became central to his rooms. I love that Frank liked to humiliate precious materials like marble, gold and mahogany by using them as pedestals for humble plaster tops.

Massive cat paws, tail-swishing fish, outsize scallop shells—even a plaster lobster phone (a Maugham commission to Salvador Dali): as fanciful and surreal as it all was, the pieces mostly focused on past traditions. As the 1960s approached, designers were looking ahead, and steel and glass dominated. Plaster’s hiatus didn’t last long, though—and in the 1970s hooved and footed plaster stools, tables and consoles reappeared, this time rendered more cartoonishly and naive by California designer John Dickinson, whose pieces have fetched eye-popping prices over the last decade. In fact, a few years back, David Sutherland began reissuing the designer’s furniture in his showrooms across the U.S.

Artists and designers on both sides of the Atlantic—particularly in France and the US—continue to celebrate the allure of plaster of Paris, each one bringing to it a synthesis of diverse influences. Marc Bankowsky‘s Magritte-like draped consoles and folding screens recall his earlier woven structures, including the net and metal beehive that stood on the Beaubourg Piazza in front of the Pompidou in 1977.

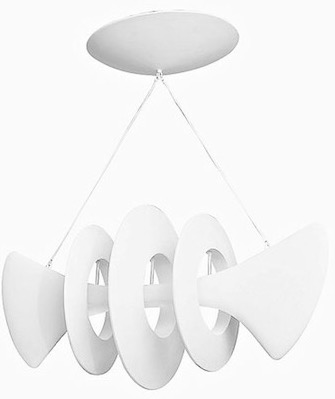

On the other hand, the chandeliers of Philippe Anthonioz, whose work was first shown in the States at interior designer Thomas O’Brien’s pitch perfect SoHo shop, Aero, in the early 1990s, suggest constructed sculptures reminiscent of Spanish artist Julio Gonzalez, who worked with Picasso on his iron, wire and sheet metal figures.

Another Frenchman, Alexandre Logé takes a more playful approach to the medium. His chandeliers channel the Dadaist Jean Arp’s biomorphic sculptures, with their cones, irregular shapes and Dr. Seussian scale shifts. His pieces remind me of the lines in Elizabeth Murray’s paintings; they’re wonderfully exaggerated with a hairpin turn thrown in here and there.

Stateside, the New York-based sculptor W.P. Sullivan has been making tables, mirrors and lighting in plaster of Paris for almost two decades. A virtuoso wood-carver, Sullivan brings a level of surface detail to his plaster pieces that have found an adoring audience in the likes of design giants Parish Hadley, Robert AM Stern and Peter Marino.

I was humbled recently when my friend Graham Shearing, the Pittsburgh-based decorative arts specialist and collector, called to check in after seeing my work in World of Interiors. As a college student, he had commissioned me to make a plaster lamp in the shape of an urn, a piece I had completely forgotten about. He later sent me a picture of the urn with a tongue-in-cheek note that read, “Early Stephen Antonson.” For the past decade, interior designers including Jeffrey Bilhuber, Daniel Romualdez, Michael Smith, Victoria Hagan, Robert Couturier and Miles Redd have commissioned my pieces. Working with plaster of Paris just does not get old. It remains compelling to me because it’s fun to push it in directions that it is not accustomed to going. Yes, there are chandeliers, mirrors and lamps, but why not a chair or even a painting? For me, there’s great satisfaction in sticking with one material and interpreting it in endless ways.

Great to read about the history of plaster and its many and varied uses. Fine article.

Great read! Thank you and congratulations.